Artists are most often inspired by the issues of their times. Art is a medium of communication, of criticism, of change—particularly when it comes to the theatre. William Shakespeare, commonly known as “the bard” was known for his eloquence and depth. His writing, though, goes deeper than flowery words and complex plotlines. As a playwright, his plays dealt with the current problems of his times, but criticizing or poking fun at the current regime is a bold and dangerous move in any society. If Shakespeare had dared to set his plays in his current time or place, his words may have never reached into this century. Writing about archaic times and far-off places allowed for the issues to be discussed more objectively. Such is the case for Titus Andronicus. This gory, raucous play is set in ancient Rome just after victory over the Goths. But this play is not just about the plights of Rome at its core. Instead, it is social commentary on the matters of the Elizabethan era (1558 – 1603 C.E.). The characters of Tamora and Aaron illustrate the racial tensions of the Roman age and echo the same strains in the Elizabethan era between the Englanders and the barbaric Moors.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word ‘barbarian’ as “A foreigner, one whose language and customs differ from the speaker's” ("barbarian, n. and adj." OED Online, Oxford University Press, September 2019). This word ‘barbarian’ exists in the modern American vernacular, but it lacks the same character that it had in ancient Rome. The word comes from the Latin word “Barbara” which has two meanings: ‘a strange land; foreign country’ and ‘an uncivilized people’. This was a term that the Roman picked up from the Greeks, who also viewed outlanders and foreigners in this way. This raw definition pulls no punches. The Romans did not discriminate when it came to the use of this word. Anyone who was not Roman was branded with this title. This is telling and gives modern societies a clue as to how the ancient Romans saw and felt about people who were not like them.

Culture is defined as “the customs and beliefs, art, way of life, and social organization of a particular country or group” ("culture", OED Online, Oxford University Press, September 2019). As most societies do, the Romans believed their culture to be the epitome of how people should live. Thus, they looked upon all other cultures as inferior and ‘barbaric’. Titus, after killing his son, Mutius, does not deign to give him a proper burial due to his mutiny (I, lines 356-61). Martius, however, appeals to Titus on Mutius’s behalf saying, “Thou art a Roman; be not barbarous. / The Greeks upon advice did bury Ajax, / That slew himself, and wise Laertes’ son / Did graciously plead for his funerals. / Let not young Mutius, then, that was thy joy, / Be barred his entrance here” (I, lines 385-90). Here, Martius wins Titus over by mentioning other cultures. His argument is thus: if barbarians such as the Greeks pay respect to their dead even in vile circumstances, then we must behave as such. His argument betrays the attitude of the Romans at that time.

England also made it very clear who was considered English and who was not. Residency in England or any surrounding lands did not make one English. The major line of distinction between the peoples of Europe, Africa, and the Middle East was religion, even before the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (Mater 63). The initial point of contention was between the English and Muslims. T. Matar writes in his journal entitled “Muslims in Seventeenth Century England”, “Muslims were not permanent residents in England (and the rest of the British Isles); nor were they subjects of the Crown because of their adherence to a non-Christian religion” (63). In this time, Muslims were commonly referred to as ‘Turks’ as a distinction between Muslims and Moors, who were native to North Africa (64). Matar continues, “Although the separation between the two groups was frequently noted, English writers treated both Turks and Moors as a single religious and cultural Other” (64).

The ‘Negars’ and ‘blackamoors’ of the sixteenth century were most certainly not English. Queen Elizabeth I was “the first English monarch to co-operate openly with the Muslims—and to grant liberty to her subjects to trade and interact with them without being liable to prosecution” (Matar 64). Most of the interactions between the Muslims or Ottoman Turks at that time were business transactions necessitated by the conflict with Spain. Gary K. Waite writes in his article entitled “Reimagining Religious Identity: The Moor in Dutch and English Pamphlets”, “Under Queen Elizabeth I, by the early 1580s England already had trade deals with the Ottoman Turks and had developed relations with Morocco” (1255). This act became a topic of controversy in England, a society that “had little experience in dealing with peoples of non-Christian faiths” (Waite 1255). Christian groups, in protest of these alliances, “revived traditional medieval Christian polemics that demonized their Muslim competitors” (Waite 1256), In 1596, Queen Elizabeth I issued several Edicts of Expulsion. This was not intended to be mass exodus of unwanted dark-skinned people from England but was instead one piece in a puzzle of negotiations with Spain. Emily Bartels writes, “when Elizabeth proposes deporting "blackamoors" from the Baskerville expedition, she is choosing subjects who have come into England as prisoners of war” (311). This later became an integral move as blackamoors in England became useful tools in bartering for English captives. The Muslims present in England at that time were not citizens, nor were they trespassers. These people were no more than bargaining chips to be used in negotiations between England and Spain (Bartels 311).

Shakespeare plays easily with the stereotypes of dark-skinned people during his time. These prejudices were heightened because of the religious aspect that often-accompanied people of different culture and skin colors. Christianity, in particular, had used the medium of theatre and performance to establish some of these deep-seated ideas. Matar writes, “The Christian association between Muslims and the devil appeared even in ceremonial events, such as the 1566 celebration over the baptism of Prince James of Scotland, during which Stirling Castle was ritually attacked by a band of highland men, Moors, and ‘devillis’” (Waite 1256). As a Moor, Aaron is also separated from his white counterparts via his religion, or lack thereof. At first, it was religion that set peoples apart in England before it morphed into a consideration of a person’s skin color as more telling. The distinction is evidenced in Aaron’s discourse with several of the characters in Titus Andronicus. When Demetrius suggests they pray to the gods for Tamora’s labor pains, Aaron shoots back cynically, “Pray to the devils; the gods have given us over” (IV, line 49). His irreligiosity is merely the icing on the cake of a character who could never amount to anything but a master of evil.

Shakespeare echoes this view of irreligious barbarians in the character of Tamora and her sons Alarbus, Chiron, and Demetrius. Tamora and her sons are spoils of war, whom Titus has brought back after victory in battle with the Goths. Tamora, though she is not a native Roman, is not ridiculed as cruelly as Aaron is. He brings back the former queen and her princes, not to be tortured or ridiculed, but to live freely in Rome as is befitting their status (I, lines 268-69). In fact, there seems to be no real issue with Tamora with regards to her foreign origins. In Act I, just after Titus’s sons bear Lavinia away from Saturninus, Saturninus takes nary a beat before asking Tamora to be his wife instead (I, lines 321-29). Of course, the proposal could not have been more perfect for Tamora and her plots of revenge. It is her fair skin and high status that earn her respect and honor, despite her being a prisoner-of-war. Titus says to her after choosing Saturninus as the new emperor, “Now, madam, are you prisoner to an emperor, / To him that for your honor and your state / Will use you nobly, and your followers” (I, lines 260-63). The word “barbarian” thus takes on a double meaning when applied to Tamora. Lavinia decries her, saying, “Ay, come, Semiramis, nay, barbarous Tamora, / For no name fits thy nature but thy own!” (II, lines 118-19). Here, the word ‘barbarous’ refers to Tamora’s base association with Aaron, the black Moor, not to Tamora’s status as a Goth. This reflects the change in thought regarding Moors and Muslims in England. The character of Tamora and her easy integration into Roman society mirrors the pacts made with Spain in the 1590s. Perhaps, Shakespeare is commenting on this turn of events. Tamora, who is quickly made Empress of Rome, becomes the seed of ruin and destruction in the empire through her plotting and scheming. This situation illustrates the folly of making bedfellows of your enemies. Soon, though, it was not the differing religion that was so abhorrent, but the color of one’s skin that set foreigners so far apart from the culture of England.

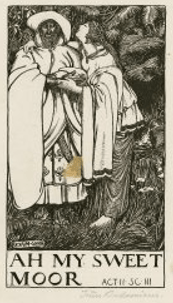

This fact is made clear in regard to Tamora’s relationship with Aaron. It is brought up as a low point, not because she is engaging in infidelity against Saturninus, but because her lover is a black Moor. In Act II, scene III when Bassanius and Lavinia confront her about her adultery in the woods, Bassanius sneers, “Why are you sequestered from all your train / Dismounted from your snow-white goodly steed / And wandered hither to an obscure plot, / Accompanied but with a barbarous Moor, / If foul desire had not conducted you?” (lines 75-79). Lavinia immediately follows suit, saying to Bassanius “I pray you, let us hence, / And let her joy her raven-colored love. / This valley fits the purpose passing well” (lines 82-84). The distinction between Tamora’s ‘snow-white goodly steed’, which may either refer to her horse or her husband, Saturninus, and her ‘raven-colored love’ illustrate just what aspect Bassanius and Lavinia deem most deplorable about Tamora and her infidelity. Had her child been born white, it would have been more easily dealt with. Aaron laments to his son, “Had nature lent thee but thy mother’s look, / Villain, thou mightst have been an emperor” (V, lines 29 – 30). Here, Shakespeare shows the scale on which an individual is measured in this society: not based on their behavior or actions, but first on their outward appearance, after which their behavior is rationalized. Tamora is just one example of how Shakespeare uses the interaction between the characters in Titus Andronicus to point out ways of thinking in his own culture. The influence and inspiration that Shakespeare took from his growing up coupled with his observance of his environment makes for dynamic characters.

Before harsh restrictions were placed on public religious dramas during the reign of King Henry VIII, Shakespeare most likely saw quite a few morality plays. These plays, according to author Stephen Greenblatt, were “secular sermons designed to show the terrible consequences of disobedience, idleness, or dissipation” (31). Protagonists with names like “Everyman” or “Mankind” would “[turn] away from a proper guide such as Honest Recreation…and [begin] to spend his time with Ignorance…” The main character would fall sway to these bad impulses until freed by Penance or Diligence (Greenblatt 32) These plays “were in vogue for a long period of time, extending into Shakespeare’s adolescence” (32). Throughout Shakespeare’s plays, key elements of these morality plays are explicit and present in his work, particularly the use of “Vice” characters. According to Greenblatt, the “Vice, wickedness personified…managed to captivate the audience, and the imagination takes a perverse holiday” (Greenblatt 34) The ‘Vice’ character in Titus Andronicus is Aaron the Moor. This inspirational background for Shakespeare’s plays in important to consider when looking at his choices in creating Aaron the Moor. It is necessary to remember that this personification of evil was present in many other Shakespeare plays, from Othello to Richard III. The question to consider then is why Shakespeare chose a black Moor to play this ‘Vice’ role. And, if Shakespeare’s task was to criticize the times and initiate reform, as is the goal of many playwrights, why make the Vice character black? Does this choice not serve to reinforce the stereotype that already existed at the time?

Initially, Aaron is pure evil. The sheer delight that he gets from ripping Titus’s family apart is frightening when considered in its fullness. Aaron is the one who devises the plots that results in the rape and mutilation of Lavinia (II, lines 119 – 125), the murder of Bassanius (II, lines 52-54), the loss of Titus’s hand (III, lines 152-58), and the killings of Martius and Quintus (III, lines 203-8). His actions, however, are not entirely without rhyme or reason. His lover, Tamora, former Queen of the Goths and current Empress of Rome, has long been his secret lover and he is enamored of her. He says, “I will be bright, and shine in pearl and gold / To wait upon this new-made emperess. / To wait, said I? To wanton with this queen, / This goddess, this Semiramis, this nymph…” (II, lines 19 – 22). His relationship with Tamora, however, is taboo because he is black Moor. While this fact matters not to Tamora, it is clear that the other characters in the play do not think highly of Aaron’s dark skin color. In Act V, scene 1, Aaron reveals the rapists of Lavinia as Chiron and Demetrius. Lucius cries out, “O, barbarous beastly villains, like thyself!” (line 99). In this case, Lucius is referring to the barbarity of their deeds is influenced by Aaron, who is a barbarian both literally and effectively.

The Edicts of Expulsion, though they were issued two years after the first production of Titus Andronicus, were the manifest of a trend in English culture that began before Queen Elizabeth I issued those edicts. As Bartels writes, “…Elizabeth's orders to deport certain "blackamoors" are, in fact, unique, for they articulate and attempt to put into place a race-based cultural barrier of a sort England had not seen since the expulsion of the Jews at the end of the thirteenth century” (305). Here, we see a shift in societal thought and perception of other cultures. England was going through its own religious upheaval at the time. As the people in power changed, so did the national religion. Suddenly, people began making distinctions between cultures based on the color of their skin and not their religious identity. According to Bartels, “Early modern scholars tend to place the emergence of a color-based racism at the end of the sixteenth century; eighteenth century scholars, at the end of the eighteenth” (306). Either way, these edicts mark the “early constructions of racism and race within English literature of the period” (Bartels 306) and a shift in attitude among Englanders. Shakespeare reflects this change in thinking in the way the white characters in Titus view the characters of Aaron. He is first seen as a black Moor, so his despicable actions are not viewed as a characteristic of his heart, but as a natural result of his complexion. It could be argued that even if Aaron did not have murder and death so engraved in his heart, the characters around him would have seen him as thus simply because of his dark skin and his ethnicity.

Social justice is “justice at the level of a society or state as regards the possession of wealth, commodities, opportunities, and privileges” ("social justice", OED Online, Oxford University Press, September 2019). The social justice issue of the treatment of dark-skinned people in Titus Andronicus lies not in a change of heart in any outside characters, but with Aaron himself. By dealing with the perceptions this way, Shakespeare challenges the motivation for Aaron’s actions and adds depth to the ‘Vice’ character of Aaron the Moor. The birth of his child is the turning point for Aaron. Suddenly, he goes from a formidable force of death and destruction to one of softness and sensitivity. As he meets his baby for the first time, he coos “Sweet blowse, you are a beauteous blossom, sure” (IV, lines 75 – 76).

Moments later, Chiron and Demetrius enter, angered that the Moor has slept with their mother (IV, lines 81 – 83). Aaron then sinks back into his diabolical side, but this time, with a much different purpose: to protect his child, “the vigor and picture of [his] youth” that he prefers “before all the world” (IV, lines 111 – 112). The violence that ensues after this episode on the part of Aaron is no longer driven by revenge against Titus or his fierce love for Tamora. Shakespeare has now put him on equal motivational footing with Titus and Tamora. Titus allows his hands to be chopped off (III, lines 189 – 190) and murders Chiron and Demetrius for the protection of his family. Tamora engineers the murder of Bassanius (II, lines 90 – 115), permits the rape and mutilation of Lavinia out of rage from her son’s murder (II, lines 179 – 180). Now the tables have turned and Aaron also has a family to cherish and protect, and he will go to great lengths to do so. Had Aaron been a wholly ‘good character’ in Titus Andronicus, this shift would have been lost. The point of Aaron’s character was not to say that dark-skinned people are none of the stereotypes that were assigned to them. Rather, the purpose and effect were to give his actions and motivations a root and a foundation in something that the audience could relate to. Most mother and fathers would do anything to protect their children. Seeing a blackamoor, a person whom they have dehumanized in their minds, displaying such a raw and human emotion that they themselves also feel, reconnects Aaron, and ultimately all blacks, with the rest of humanity in a powerful and emotional way.

These circumstances, however, prompt an important question: if the Roman characters of Titus Andronicus view Aaron as a wicked black Moor barely fit to live, why is it that all of the characters listen to him and do his bidding? The answer lies not in action but in word. Bartels writes, “What threatens to undermine Aaron's function as an absolute sign of the Other is his cultural literacy, his knowledge of classical mythology, and his eloquence” (The Making of the Moor, 444). When Aaron first speaks, his superior command of language is immediately made manifest. As he declares his love for Tamora, he compares her ascent to the throne to

"[climbing]…Olympus’ top / safe out of Fortune’s shot…

[advancing] above pale Envy’s threat’ning reach

As when the golden sun salutes the morn

And, having gilt the ocean with his beams,

Gallops the zodiac in his glistering coach

And overlooks the highest-peering hills…" (II, lines 1-8).

As mentioned previously, culture was of the utmost importance to the Romans; their lives and conduct were governed by their religion and their laws. What would they think, then, of a foreigner who has knowledge of their beliefs and can speak fluently about them? Aaron’s “ability to speak of gods and goddesses, to decipher Latin, and to imagine the world as myth integrates him to some degree into the community of Romans and Goths” (Bartels 445).

The commonality, then, is found not in appearance but in intellect. Aaron thinks like a Roman; therefore, the things that come out of his mouth are believable to a Roman. This may explain why the Roman characters so readily take Aaron’s advice and listen when he talks despite the color of his skin. What sets him apart as a foreigner is not a lack of culture or refinement but his “blackness” both inside and out.

The characters of Titus Andronicus, however, only see one side of the coin. Though Aaron has shown the audience his humanity, through his care for his child and his vehement declarations of pride and beauty in his skin color, the characters around him are unable to look past his color and the prejudices they possess in reaction to it. When Aaron argues for the boy’s life on the grounds of nobility, a status that afforded even Tamora, a Goth, honor and respect among the Romans, Lucius spits back “Too like the sire for ever being good” (V, line 50). “Too like the sire” in neither word nor deed, for it is but a child, but in appearance. The child should be put to death because it is black and therefore is inherently evil. In the end, as Aaron is lead offstage to his death, he says,

Ten thousand worse than ever yet I did

Would I perform, if I might have my will.

If one good deed in all my life I did,

I do repent it from my very soul (V, lines 189-92).

From the moment Titus and the Romans steps on stage, heads roll and blood runs. After the news of Alarbus’s murder, Chiron mutters under his breath to his mother and brother, “Was never Scythia half so barbarous?” (pg. 17). Soon after this murder, Titus commits another, stabbing his son Mutius for disrespect (I, lines 295-98). Though Aaron’s master manipulation and wanton displays of cruelty “[reveal] a purposelessness that makes his villainy all the more insidious” (Bartels 445), he is arguably no more cruel than Titus. Even Lucius, Titus’ son, is appalled when Titus murders his son Mutius for disrespecting him. Lucius cries, “My lord, you are unjust, and more than so! / In wrongful quarrel you have slain your son” (I, lines 298-99). This prompts another question: Would Aaron’s attitude toward Titus and his family been different, or perhaps mollified, if it were not for their insistence on his viciousness because of his looks? Is this unadulterated evil or a case of “If you can’t beat them, join them?”

From Greek tragedy to Japanese Kabuki, artists around the world have been using theatre as a powerful medium for exploration and change in society. For all his robust language and intricate storylines, William Shakespeare was no exception. He used Titus Andronicus and the relationship between its characters to illustrate the issues present in his time. The characters of Tamora and Aaron collectively represent the shift in English thinking from religion as a marker of distinction to race. Yet, despite Aaron’s black skin that defines him as “Other”, his persuasiveness and articulacy afford him an ear in the Roman court. Here, he is able to work Tamora’s vengeance. His character is complex—a fact brought out with the introduction of his son. Suddenly, Aaron’s violence is channeled into one lofty goal—protection of those he loves. This trait, this virtue of the Vice, is something that the audience could relate to.