Eurydice in History and in Sarah Ruhl’s Play

By Lillie Kortrey 2022-2023 Dramaturgy Production Intern

There is very little historical information on Eurydice. Encyclopedia Britannica gives the following brief description of Eurydice: “Eurydice, in ancient Greek legend, the wife of Orpheus. Her husband’s attempt to retrieve Eurydice from Hades forms the basis of one of the most popular Greek legends. See Orpheus.”

This is precisely why playwright Sarah Ruhl investigated the myth in its ancient origins as well as its more contemporary interpretations to tell Eurydice’s version of the classic Orpheus story. There is an abundance of information on Orpheus and this myth as often referred to as simply, “the Orpheus story.” Classical authors like Plato, Ovid, and Virgil, as well as contemporary writers, like Jean Cocteau and Tennessee Williams, all tell similar stories of Orpheus and have very little to say about Eurydice.

The earliest account of the Eurydice and Orpheus myth comes from 530 BCE from the ancient Greek poet Ibycus. The classical Greek myth names Orpheus the most talented musician in the world who possesses god-like qualities. He is the son of Calliope, a muse and goddess of literature, science, and the arts who presides over eloquence and poetry, and Apollo, the god of music, poetry, art, prophecy, truth, archery, healing, and more. Some versions cite Oeagrus, a king of Thrace, who had no god-like ability as Orpheus’s father. Apollo gave Orpheus his first lyre, on which he played music that enchanted all who heard it, as well as nature. Before his trip to the Underworld, Orpheus was heralded as a hero as he is believed to have taken part in an expedition of the Argonauts, or band of 50 heroes, in the obtaining of the Golden Fleece, a winged ram that had the power to charm any living thing plant, animal, demigod, or mortal. Orpheus was vital to this quest as he saved the Argonauts from music of the Sirens by playing his own.

Orpheus’s first love was music, something that Ruhl maintains in her version of the story, and he spent his early years in the pursuit of music and poetry. He mastered music in his youth, and his beautiful lyre playing as well as his singing voice often attracted large crowds. One day, in one of the crowds his music garnered, he spotted Eurydice, described as a nymph or maiden who personified nature. Eurydice and Orpheus were soon married. Happiness soon turned to grief when Eurydice died as a result of a snake bite on her wedding day. Dismayed by her death, Orpheus charmed Hades, god of the Underworld, into making a deal with him that involved his entrance into the Underworld to bring Eurydice back into the world of the living. Hades permitted Orpheus into the Underworld and promised Eurydice would follow Orpheus back up to Earth, if he did not, under any circumstances, look back at her. Overjoyed that he would be reunited with his love, Orpheus took to the Underworld. He soon heard Eurydice’s footsteps behind him. As much as he wanted to turn around to reunite with Eurydice, Orpheus controlled his impulses. It was not until the pair reached the threshold of Earth that Orpheus looked back at Eurydice, only to catch a glimpse of her before she disappeared, this time permanently. Heartbroken, Orpheus wandered around Greece, keeping to himself and rejecting the advances of other women. His once joyous songs were now sorrowful. A group of women from Thrace noticed Orpheus and remembered his rejection of them. Scorned by this memory, the women used stones, spears, and branches to kill him. After his death, they cut his body into pieces and threw his lyre into a river. As a result, Orpheus ended up in the Underworld where he was reunited with Eurydice.

Sarah Ruhl rejects Eurydice’s role as prop or vehicle in the original Greek myth as well as subsequent interpretations that have been told and retold throughout centuries. Ruhl tells the story from Eurydice’s perspective, exploring her relationships both on Earth and in the Underworld, putting her in control and making her own decisions. Ruhl’s interpretation follows Eurydice as she faces love, loss, and grief in her journey through the Underworld. Throughout the play, Eurydice is exploring the different relationships with the men in her life, Orpheus and her father. She is stuck between two different worlds and two different expressions of love, familial and romantic. She finds her own identity independent of the men in her life. Orpheus comes to the Underworld to bring her back to Earth, but it is ultimately Eurydice’s decision to stay there.

This myth has been subject of many classical as well as contemporary interpretations. In the Ancient Greek world Ovid and Vergil most notably, told their own versions of the Orpheus myth. Book X of Ovid’s Metamorphoses recounts the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, though Eurydice’s name is hardly mentioned. In this version, as well as several many others, Orpheus is the hero, reclaiming a helpless Eurydice, and it is Orpheus, who seals her fate to remain in the Underworld permanently. His story is maintained as heroic throughout. Ovid continues to tell Orpheus’s story after the permanent disappearance of Eurydice. In Book X, Ovid tells the story of Cypresses. (Ovid/ Book X/ lines 121-155/ pages 237-238). In this part of Orpheus’s tale, he sits on a plateau and begins to play his lyre. This, of course enchants the nature that surrounds him, and Orpheus soon learns that one of these trees used to be a boy named Cyparissus. As a result of his death, Apollo turned the boy into a tree that all could mourn under. (Ovid/ Book X/ lines 132-136/ page 237). Although this story is unrelated to the classical interpretation of Eurydice, it is relevant in Ruhl’s Eurydice. When Eurydice first arrives in the Underworld she does not recognize anything or anyone as a result of passing through the River Lethe, or the River of Forgetfulness in Greek mythology. Despite her father telling her exactly who he is, Eurydice still does not recognize him until he states, “when I was alive, I was your tree,” (Movement Two/ Scene One/ Page 30). In this instance, Ruhl remains true to ancient roots of the dead in the form of a tree, as this same theme is present in the story of Daphne, who was a Greek dryad or tree spirit, who was transformed into a laurel tree, according to Encyclopedia Britannica.

What is also revenant to Ruhl’s Eurydice, is the song Orpheus sings while under the tree. His song states,

“A gentler lyre, for I would sing of the boys

Loved by the gods, and girls inflamed by love

To things forbidden and earned punishment,” (Ovid Book X/ lines 154-156/ page 238).

This song suggests that boys are lovable and girls destructive. Boys inspire the love of the gods, while girls have been punished for their wild passions. Ruhl’s Eurydice actively defies this claim. While Orpheus and Eurydice and both passionate in Ruhl’s Eurydice, Orpheus about music and Eurydice about books and language, it is ultimately Orpheus’s wild passion to reclaim Eurydice that is the most destructive. He not only becomes increasingly distraught on Earth through his selfish endeavor, but he is more of an intruder than anything else with his visit to the Underworld. What he thinks is an act of heroism, actually has dire consequences not only for himself, but for Eurydice and her father as well. Eurydice’s passion on the other hand, results in a tender relationship with her father, that ultimately allows her to make her own decision to stay in the Underworld with him.

Eurydice and Orpheus in Art

Inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Nicolas Poussin, a famous Renaissance painter popular in the classical French Baroque style, depicts the moment Eurydice dies as a result of a snake bite at her wedding in Landscape of Orpheus and Eurydice, painted between 1650-53. Orpheus is distracted by the music he is creating with his lyre and does not yet notice Eurydice’s misfortune. Eurydice is the leftmost figure in the foreground surrounding Orpheus who is in red, playing his lyre. She is the figure in the yellow, who is kneeling down with her arm out as if to push away her surroundings. Looking very closely at the image, one can see the snake that has bitten Eurydice is still slithering in the grass near her hand. Eurydice is looking into the darker, shadowed left corner of the painting revealing an interesting juxtaposition between the way the couple views life. Eurydice looks more ominous, as do her surroundings. This reveals how she is cognizant of the hardship life has to offer and what she will ultimately succumb to when she dies on her wedding day. Orpheus, on the other hand, is oblivious to the impending darkness both presently in his surroundings, and later when he loses his wife. Although the title suggest that this painting is solely focused on Orpheus and Eurydice, Eurydice is almost invisible. She is surrounded by several other women, who have gathered to hear Orpheus play his lyre. Her ability to blend in with the crowd exacerbates Eurydice’s passive role as a prop in Orpheus’s story. Additionally, what catches the viewers’ eyes are all the figures in the background and what activities they are engulfed in. While there is no precise meaning assigned to these figures, they are included because, according to the article, The Landscape Demythologized: From Poussin’s Serpents to Fenelon “Shades” and Diderot’s Ghost by Walter E. Rex, it is indicative of Poussin’s intention to not draw attention to one or two central figures, but to the landscape as a whole. This creative and artistic skill brings eeriness and mystery to the scene and opens the classic myth up to interpretation.

This painting is relevant to Ruhl’s Eurydice, as Ruhl strayed from the classical myth to tell Eurydice’s story, making her an active figure, rather than a prop in Orpheus’s story. This painting can reveal what Ruhl highlights as the differences between Eurydice and Orpheus. Eurydice is much more practical than Orpheus. She values words and books, whereas her husband has his head in the clouds and is said to be “always thinking about music.” This is ultimately why Eurydice decides to not return to Earth with Orpheus. They are too different. Their passions don’t align.

This 1862 painting by Sir Edward John Poynter is titled Orpheus and Eurydice. As the title suggests, the painting depicts Orpheus and Eurydice as Orpheus takes her out of the Underworld. Traditional interpretations of this painting have credited Orpheus as a hero saving Eurydice from the Underworld and leading her out, however, I see it differently. By playing Eurydice in Theatre Fairfield’s production, I have spent a lot of time with her and have gotten to know her quite a bit and have learned a lot about her. I admire how she was able to find herself without Orpheus and I admire how she was brave enough to make the choice to stay in the Underworld on her own terms. To me, this painting supports Eurydice’s choice. It does not look so much like Orpheus is leading her to the Overworld but dragging her back to be with him. Forcing her to be with him in this way completely erases the independence that Eurydice has worked so hard to establish, therefore doing her a disservice. This painting further emphasizes the point Ruhl rejects: Eurydice’s passive role in the classic myth. She is so much more than a prop in Orpheus’s story, she is her own intelligent, kind, compassionate, and loving person with or without Orpheus.

Pictured above is a drawing titled Orpheus and Eurydice by Ludwig Thiersch created in 1884. The image depicts the moment when Orpheus looks back at Eurydice after descending into the Underworld to bring her back to Earth. Right as he was about to enter the world of the living, Orpheus looked back to ensure Eurydice was following him, going against the instructions of Hades and consequently losing Eurydice over again. Orpheus reaches his arms out in despair, though it is too late. Mercury, god of translators and interpreters, is pictured on the right ushering Eurydice back through the river where she would remain in the Underworld without her husband. According to Greek Mythology, there are five rivers in the Underworld. They include Styx, River of Hatred; Acheron, River of Woe or Misery; Phlegethon River of Fire; Cocytus, River of Wailing, and Lethe, River of Forgetfulness. Upon entering the Underworld, the dead would travel through the River Lethe and forget their Earthly existence, as Eurydice did in Ruhl’s interpretation. She forgets all that is known to her and has to relearn while rediscovering herself in the Underworld.

Sarah Ruhl

Sarah Ruhl is an award-winning American playwright, essayist, author and professor. Her most notable plays

include The Clean House, The Oldest Boy, Dear Elizabeth, Stage Kiss, and In the Next Room (or The Vibrator Play),

which was a 2010 Pulitzer Prize finalist. Ruhl’s plays have been produced all over the country on Broadway, Off-

Broadway, Lincoln Center, the Goodman Theatre, Berkeley Repertory Theatre, and throughout the world. She received her MFA in playwriting at Brown University where she studied under award-winning American playwright, Paula Vogel (How I Learned to Drive, Indecent). Ruhl won the MacArthur Fellowship, so-called Genius Award, in 2006, the Feminist Press’s Forty under Forty award, and the Steinberg Distinguished Playwright Award in 2016. Ruhl is currently on the faculty at the Yale School of Drama. She has also authored a number of books, including several volumes of poetry, most recently Love Poems in Quarantine, reflecting on life during the COVID-19 pandemic, and a 2021 memoir Smile: The Story of a Face which discusses her journey with Bell’s Palsy, which is a neurological disorder that causes paralysis to one side of the face.

Her most recent play, Letters from Max, is based on her 2018 book, co-authored with Max Ritvo, Letters from Max: A Poet, a Teacher, a Friendship. The Eurydice company went to see the play at the Signature Theatre in New York City. The play is a series of letters between her and her student, fellow poet, and friend Max Ritvo, as they openly discuss Max’s terminal illness, and what comes after life, through poetry and music to put the unknown into words. After the show, the company had the opportunity to listen to Sarah Ruhl give a talk back about her process transforming her book into a staged play.

Eurydice Production History

Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice premiered at the Madison Repertory Theatre in Madison, Wisconsin in 2003. A year later, the play ran at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre, followed by a 2006 run at the Yale Repertory Theatre. Eurydice opened off- Broadway in 2007 at the Second Stage Theatre where it was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in the same year. Upon its 2006 debut, the play received great reviews by major media publications like The New Yorker and the New York Times, which named the play one of the 25 most important plays since Angels in America.

In February 2020, Ruhl adapted her play into a libretto for an opera of the same name, composed by Matthew Aucoin and staged by renowned director, Mary Zimmerman, which premiered at the L.A. Opera and then became part of the Metropolitan Opera’s 2021-22 season. Like the play, the opera reimagines the original myth from Eurydice’s point of view. When asked what she’d like a young viewer to bring to the show, Ruhl responded, “I’d love for them to bring their own experiences of having lost someone they love, their own questions about what the afterlife could look like, or their own questions about the power of music or art to reach the dead. I think there’s something about myth that allows you to understand it through your own individual experience—and I think that’s true of opera in general. What’s incredible about opera is that the scale is so large that you don’t see a direct reflection of reality. You’re seeing massive imagery—it’s almost a dream logic. So, I’d invite the students to dream their way into it.”

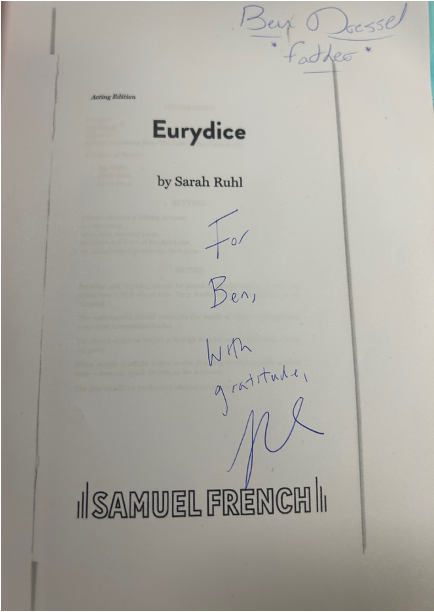

Ruhl is currently enjoying a Signature Theatre Playwrights’ Residency where Letters from Max is still running. A staged reading of Eurydice, with the original director, Les Waters, at the helm will be presented for the Signature’s 2023 Gala on April 23, the day after our production closes. The cast also had an opportunity to meet her and Eurydice actor, Ben Dressel, who plays the Father, had his script signed by Ruhl. When we met her, Ruhl hinted that a major new production of Eurydice may be forthcoming; we think the reading may

be its beginning.

Bibliography

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Eurydice." Encyclopedia Britannica, February 8, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Eurydice-Greek-mythology.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Orpheus." Encyclopedia Britannica, November 29, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Orpheus-Greek-mythology.

Greeka.comm. “Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice - Greek Myths: Greeka.” Greekacom. greekacom. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.greeka.com/greece-myths/orpheus-eurydice/.

Rex, Walter E. “The Landscape Demythologized: From Poussin’s Serpents to Fénelon’s ‘Shades,’ and Diderot’s Ghost.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 30, no. 4 (1997): 401–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30053867.