The Thanksgiving Play Digiturgy

From The Washington Post:

This tribe helped the Pilgrims survive for their first Thanksgiving. They still regret it 400 years later.

Playwright Profile: Larissa FastHorse

Mikaela Pratt (2024)

Born of the Sicangu Lakota Nation, Larissa FastHorse is a famed playwright and MacArthur “Genius Award” Fellow. She started as a ballet dancer before moving to stage and television writing. FastHorse also founded Indigenous Direction, a consulting firm that advises on media projects that deal with Native American issues and representation, as well as how non-Native people can build healthy relationships with indigenous communities.

The Thanksgiving Play, one of the top ten most-produced plays in the United States for the past four years, is her first play which features exclusively white characters. In an interview with American Theatre magazine, FastHorse explained her frustration with predominantly white theatre companies not putting on her plays because they claim they can’t find Native American actors to fill the roles; hence, her choice to write a play exclusively for white actors.

A frequent topic in the interview concerns her difficulties with white audiences and how they engage with her work. Part of her frustration that motivated her to write The Thanksgiving Play was how being native and a playwright who writes about native people often has white liberal audiences look to her and her work for educational purposes: “Oh, wow. I can learn something about Indigenous folks.” Another annoyance she highlighted was the white guilt from her audiences who ask, “I laughed—is that okay? With this particular play people understand laughing at the white parts. They get very uncomfortable when they get closer to the Native things, or showing some of the ways that white people appropriate everything, including our tragedy and pain. When we get to those parts, that’s when it’s interesting: The white people get really nervous and scared about laughing, and the Native people laugh the hardest, because it’s so true, and you have to laugh or you would cry, you know?”

“As an Indigenous human,” FastHorse argues, “once I’m in that theatre, then my job is to advocate for the play, advocate for myself as an artist, but then also advocate for my community. Because I can’t be the last Native person in that door. So I will fight tooth and nail for the community; I will do whatever I have to do to defend them,

and make sure that the access stays open.”

For more information on FastHorse and her work, go to these websites:

https://www.hoganhorsestudio.com/bioandphotos https://www.macfound.org/fellows/class-of-2020/larissa-fasthorse

https://www.indigenousdirection.com/services

Acknowledging the Land and Local Native American History

Lillie Kortrey (2023)- 2021-2022 Dramaturgy Production Intern

The following is an abbreviated excerpt from Charles Brilvitch’s book,

A History of Connecticut’s Golden Hill Paugussett Tribe

(Charleston: History Press, 2007). Brilvitch is a Bridgeport, Connecticut historian, and an expert on the architectural history of the City.

A History of Connecticut’s Golden Hill Paugussett Tribe,

details information about the Paugussett tribe, one of the Indigenous tribes that occupied land all around Fairfield County. It is important to acknowledge the people who came before us and understand their culture and history. Theatre Fairfield acknowledges that we reside on land originally belonging to The Golden Hill Paugussett tribe, among several other Indigenous tribes.

The Thanksgiving Play heavily emphasizes the importance of lifting up and empowering Native voices that have been silenced and neglected throughout history. Understanding the history of the Paugussett tribe, prior to and post European settlement is a way for non-Native spectators to show respect and honor to the Native point of view.

“The Golden Hill Paugussett tribe has been a part of Greater Bridgeport’s history from time immemorial. The original indigenous people of this region, who greeted the European explorers and settlers and who were responsible for the pottery fragments, arrowheads, and shell middens excavated by archaeologists over the years, still manage to hold onto a tiny scrap of their ancestral territory, the Golden Hill Reservation in Trumbull.

Scholars and historians generally agree that Paugussett territory extended along the Connecticut coast west from New Haven Harbor to the Saugatuck River in Westport, and to the upper reaches of the Housatonic and Naugatuck Rivers. This is a unique geological province of Connecticut: It is the only portion of the state with a wide and fertile coastal plain, much like lands well to the south (to the east of New Haven and from Norwalk west the boulder-strewn granite hills extend down to the edge of the Sound). The Paugussett lands had long sandy beaches adjoined by extensive tidal flats and salt marshes, quite the opposite of the “rock-bound coast” usually associated with New England.

This gentle land was a paradise for shellfish, and wildlife as well as Native people. It is estimated that then, as now, fully 25 percent of Connecticut’s oyster population could be found at the mouth of the Housatonic River–and the area immediately off the coast of Bridgeport comprises the largest natural-growth oyster bed to the north of Chesapeake Bay.

The Paugussett tribesmen nurtured the terrestrial component of this coastline as well. They used fire as a tool to clear underbrush, add fertility to the soil, and provide optimal conditions for game animal habitat. They also cleared substantial areas to create major planting–indeed, the contact-era name for what is now Bridgeport, “Pequonnock,” means “cleared land.”

Europeans began to explore the coast in the 16th century, transmitting deadly diseases that spread from tribe to tribe for which the Natives had no resistance. In 1614 Dutch traders set up shop on the Hudson River, a mere 50 miles from Paugussett territory. Within a short time, they managed to coerce the tribe into intensive manufacture of wampum, a product of the quahog shells found in profusion in the waters off the beaches of Fairfield, Milford, and Bridgeport. Used by Natives for millennia for religious and diplomatic purposes, the wampum belts became perverted into a form of currency that was used in the fur trade centered at Albany. The peaceful Paugussett, whose few primitive weapons were useless against the firearms possessed by the Dutch, were in no position to refuse.

It would not be long before the choice lands that were home to the Golden Hill Paugussett caught the eye of the land-hungry Englishmen. Led by their clergymen, Puritan flocks helped themselves to the rich farmland of the Connecticut River Valley–the product of countless generations of toil on the part of the River Indians–beginning in 1633. The docile River tribes folded before the English, but another more warlike tribe–the Pequots–stood their ground and contested the Puritan incursion into Indian territory. Their resistance led to the Pequot War of 1637, in which the majority of the tribe regardless of age, gender, or history of taking up arms against the English, were murdered in their sleep, and much of the remainder found themselves enslaved, some thousands of miles from home.

A tattered remnant of the Pequot tribe fled overland, hoping to hook up with kinsmen in the Hudson Valley. They covered 80 grueling miles on foot before they were cornered by the English in a swamp in what is today known as Southport (between Center Street and Oxford Road, just to the north of the I-95 entrance ramp). Here most of the remaining warriors were slaughtered. With the Pequot tribe vanquished, the Englishmen took a good calculating look at the land in the vicinity of their battlefield and liked what they saw–lots of level, fertile land already cleared and ready to farm, plenty of salt hay for their cattle in the marshes, and all those fish and oysters. Accordingly, two years later three new settlements were planted–Milford, Stratford, and Fairfield right in the middle of the Paugussett heartland. As had been the practice elsewhere, the Indian inhabitants would simply have to be elbowed aside from their own country.

The Paugussett people, far from being hapless and perpetual victims, adapted themselves with courage and panache to their new circumstances and took for themselves a page out of the white man’s playbook. They not only survived; they prospered, and in many ways laid the groundwork for the modern community that we all know. The Native population had basically been forced in its entirety off the reservations and had adapted Christianity and Anglo-Saxon surnames and outward lifestyles. They spoke English fluently in their public and private life. They remained eminently conscious, however, of who and what they were, their cultural heritage amazingly intact beneath a veneer that was acceptable to their white neighbors. They generally supported themselves as farmhands, millhands, woodcutters, and general laborers in the country towns throughout the region.”

All information from: Brilvitch “The Golden Hill Paugussett Tribe.” Bridgeport History Center. Accessed October 8, 2021. https://bportlibrary.org/hc/grassroots-historians/.

Notes on the First Thanksgiving

Claude Scales, a good friend of Theatre Fairfield and author of the popular blog, Self-Absorbed Boomer, shared his Thanksgiving Day post 2010, "Thanksgiving is a Contested Holiday. Enjoy it Anyway" in anticipation of our production of The Thanksgiving Play. With Claude's kind permission, his assiduous research and witty musings on the real first Thanksgiving is provided in full below. Thanks, Claude, for your good humor and fascinating information!

- Dr. Martha S. LoMonaco

"First off, let's talk turkey. Actually, let's discuss whether we should be eating turkey at all. Back in the early 1980s, Calvin Trillin wrote a piece titled "Spaghetti Carbonara Day", later anthologized in Third Helpings (1983) and in The Tummy Trilogy (1994). The gist of his argument is as follows:

In England, along time ago, there were people called Pilgrims who were very strict about making everyone observe the Sabbath and cooked food without any flavor and that sort of thing, and they decided to go to America, where they could enjoy Freedom to Nag. The other people in England said, "Glad to see the back of them." In America, the Pilgrims tried farming, but they couldn't get much done because they were always putting their best farmers in the stocks for crimes like Suspicion of Cheerfulness. The Indians took pity on the Pilgrims and helped them with their farming, even though the Indians thought that the Pilgrims were about as much fun as teenage circumcision. The Pilgrims were so grateful that at the end of their first year in America they invited the Indians over for a Thanksgiving meal. The Indians, having had some experience with Pilgrim cuisine during the year, took the precaution of taking along one dish of their own. They brought a dish that their ancestors had learned from none other than Christopher Columbus, who was known to the Indians as "the big Italian fellow." The dish was spaghetti carbonara--made with pancetta bacon and fontina and the best imported prosciutto. The Pilgrims hated it. They said it was "heretically tasty" and "the work of the devil" and "the sort of thing foreigners eat." The Indians were so disgusted that on the way back to their village after dinner one of them made a remark about the Pilgrims that was repeated down through the years and unfortunately caused confusion among historians about the first Thanksgiving meal. He said, "What a bunch of turkeys!"

But, were the Pilgrims (who weren't actually called that until some years after 1620) really such an unpleasant lot? David D. Hall, a professor at the Harvard Divinity School, in his op-ed piece

“Peace, Love and Puritanism” in yesterday's

New York Times, blames their bad rep in part on a novel written many years after they arrived:

Nathaniel Hawthorne, who came along a couple of centuries later, bears some of the blame for the most repeated of the answers: that Puritans were self-righteous and authoritarian, bent on making everyone conform to a rigid set of rules and ostracizing everyone who disagreed with them. The colonists Hawthorne depicted in “The Scarlet Letter” lacked the human sympathies or “heart” he valued so highly. Over the years, Americans have added to Hawthorne’s unfriendly portrait with references to witch-hunting and harsh treatment of Native Americans.

Hall then argues:

Contrary to Hawthorne’s assertions of self-righteousness, the colonists hungered to recreate the ethics of love and mutual obligation spelled out in the New Testament. Church members pledged to respect the common good and to care for one another. Celebrating the liberty they had gained by coming to the New World, they echoed St. Paul’s assertion that true liberty was inseparable from the obligation to serve others.

Ah, but here's another point of controversy: did this notion of an "obligation to serve others" manifest itself in a kind of pre-Marxian "socialism" that, as argued by some "conservative"* writers in recent years, led to indolence and crop failure which was alleviated by a decision to allow individuals or families to own and farm private property, thereby giving them the incentive to produce more and leading to the bumper crop that was the basis for the first Thanksgiving feast? The British historian Godfrey Hodgson observes of this argument, in his article

"Thanksgiving and the Tea Party" in

openDemocracy, that "there is a certain historical basis for it."

When the settlers had first arrived at Plymouth, all their slender property was held in common, and food distributed to each according to his need. In spring 1623, they decided to allow each family to grow its own food on its own plot. [Edward] Winslow [one of the settlers who arrived on the

Mayflower] describes the motive thus: “considering that self-love, wherewith every man, in a measure more or less, loveth and preferreth his own good before his neighbour’s, and also the base disposition of some drones”.

Hodgson notes, contrary to Hall's suggestion of a religious motive for the holding of property in common, that

...[A]ll of them, godly or profane, were engaged in a capitalist enterprise. They had borrowed money for the expedition from financiers who would have to be repaid. Their agreement over sharing land and property was the internal arrangement of a company of adventurers, of whom there were many such in 16th and 17th century England; this one just happened to include men and women with religious convictions.

Kate Zernike in her November 20

Sunday Times article,

"The Pilgrims Were...Socialists?", quotes New York University historian Karen Ordahl Kupperman concerning a similar common holding agreement among the settlers of Jamestown, Virginia: “It was a contracted company, and everybody worked for the company. I mean, is Halliburton a socialist scheme?”

There is also dispute over the timing and nature of the first Thanksgiving feast. Hodgson notes that there are two extant accounts of the earliest years of the Plymouth settlement written by original settlers. One of these,

Good Newes from New England, by Winslow, was published in 1624, just four years after the Mayflower arrived; the other,

Of Plimothe Plantation, by William Bradford, governor of the colony, was written and published a quarter of a century later. Both Winslow and Bradford, the latter perhaps relying on Winslow's earlier account, describe an event in the summer of 1623, which Hodgson summarizes thus:

A drought causes the crop planted by the settlers - corn and beans - to fail. They respond by humbling themselves before the Lord in prayer and fasting. “Oh, the mercy of our God”, Winslow writes, “the clouds gathered together on all sides, and the next morning distilled such soft, sweet and moderate showers of rain” that the corn and the beans revived. The settlers thank their God for His mercy.

This comports with the notion of the motive for the first Thanksgiving: gratitude to God for a good harvest. It also fits with the "Tea Party" account chronologically, since the "common course" of property holding was abolished by Bradford in the spring of 1623. Nevertheless, it doesn't support the notion that a newfound industriousness on the part of the settlers caused a bumper crop; instead, it was a change in the weather that the settlers ascribed to their pious supplications to God.

The other account, as found in Bradford's narrative, agrees more closely in its details to what has become the traditional Thanksgiving story, in that it takes place late in 1621 and involves Native American guests. Hodgson describes it as follows:

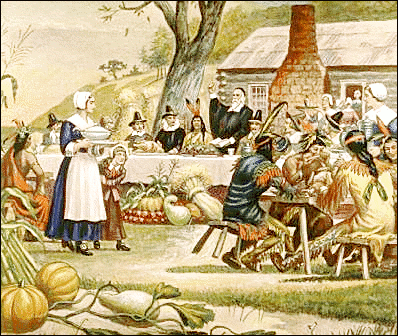

Bradford’s account [is] of a feast in 1621 - a sort of frontier diplomatic dinner - between the people Bradford later called “Pilgrims” and the local “Indian” tribe and their “king”, Massasoit. Bradford describes how the colonists sent four men out to hunt, who returned with a large quantity of “fowl” (not necessarily turkeys); and how the Indians contributed the carcasses of five deer. That event is widely remembered as the First Thanksgiving (see [Hodgson's] A Great and Godly Adventure: The Pilgrims and the Myth of the First Thanksgiving [PublicAffairs, 2007]).

Randy Patrick, in "The Myth of the First Thanksgiving," relying on Hodgson's

A Great and Godly Adventure, notes that the Native Americans were party crashers, not invited guests.

When about 100 Wampanoag warriors showed up uninvited at the Pilgrims’ festival with freshly killed deer as a gesture of goodwill, they were angling for a treaty with the Anglo-Saxon tribe.

Patrick also notes Hodgson's "convincing" argument that the 1621 feast was not one of "thanksgiving" to God, but rather (quoting from

A Great and Godly Adventure):

...“a harvest-home celebration, of the kind familiar from centuries of observance in rural England, interrupted by a force of Indians …”

In the first place, Hodgson says, the Separatists (they weren’t called Pilgrims) showed their gratitude to God not by feasting, but by fasting.

Being radical Protestants, they didn’t celebrate holy days (i.e. holidays) such as Christmas and Easter, because they considered them superstitious relics of Catholicism.

Being English, however, they did celebrate the secular Medieval harvest festival, which involved eating, drinking beer and wine, and playing games.

However, Patrick disputes Hodgson's contention that turkey was not likely to have been on the menu because they were scarce in the vicinity of Plymouth. He cites Nathaniel Philbrick's Mayflower (2006), which quotes Bradford to the effect that wild turkeys were abundant in the area, and that the settlers hunted them in winter when they could track them in the snow.

One thing’s for sure: If the Pilgrims did encounter a turkey, they would know what it was because the Spanish had introduced the American species to Europe by way of the Ottoman Empire (thus the name “Turkey”) in the time of the conquistadors. By the 1620s, it was a familiar dish on the English table.

As for the pumpkin pie and cranberry sauce, Hodgson says, the English colonists didn’t have sugar until decades later.

So, what can we conclude from all this? Attempts to use history to prove gastronomic, political, or religious contentions must always be examined carefully. Meanwhile, enjoy your turkey with all the trimmings."

- Claude Scales, "Thanksgiving is a contested holiday. Enjoy it anyway."